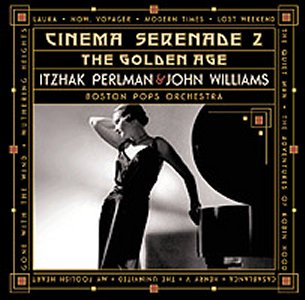

Track Listing

01. Laura (1944):

Theme (3:14)

DAVID RAKSIN, Arr. Angela Morley

02. Now, Voyager (1942): Theme (5:03)

MAX STEINER, Arr. John Williams

03. Modern Times (1936): Smile (3:39)

CHARLIE CHAPLIN, Arr. John Williams

04. Lost Weekend (1945): Love Theme (4:18)

MIKLÓS ROSZA, Arr. John Williams

05. The Quiet Man (1952): St. Patrick's Day (2:17)

Traditional, Arr. Angela Morley

06. The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938): Marian & Robin Love Theme

(4:04)

ERICH KORNGOLD, Arr. John Williams

07. Casablanca (1942): As Time Goes By (4:18)

HERMAN HUPFELD, Arr. John Williams

08. Henry V (1944): Touch Her Soft Lips and Part (4:00)

WILLIAM WALTON, Arr. Richard Rodney Bennett

09. The Uninvited

(1944): Stella by Starlight (5:09)

VICTOR YOUNG, Arr. John Williams

10. My Foolish Heart (1949): Theme (3:43)

VICTOR YOUNG, Arr. Angela Morley, Words by Ned Washington

11. Gone with the Wind (1939): Tara's Theme (3:33)

MAX STEINER, Arr. Angela Morley

12. Wuthering Heights

(1939): Cathy's Theme (3:42)

ALFRED NEWMAN, Arr. Angela Morley

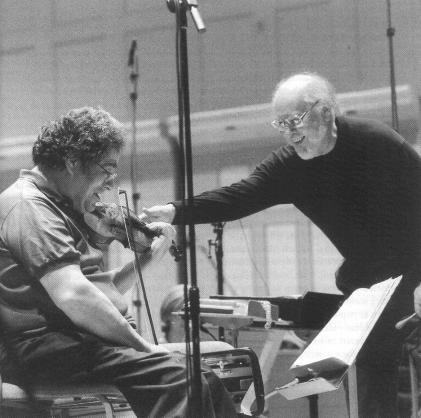

John Williams and Itzhak Perlman

The most romantic, glamorous

themes from the greatest years of Hollywood film music are brought thrillingly to life in

this new collection from Itzhak Perlman and John Williams, the follow-up to their

bestseller Cinema Serenade.

Composers such as Victor

Young, Max Steiner, Alfred Newman, Miklós Rózsa, Erich Korngold and William Walton wrote

unforgettable music for classic films like Casablanca, Gone with the Wind,

Wuthering Heights, Laura and Now, Voyager. Itzhak Perlman gives

them passionate new interpretations in these new arrangements for violin and the legendary

Boston Pops Orchestra by John Williams, Angela Morley and Richard Rodney Bennet.

The first Cinema Serenade collection (still on Billboard's Classical

Crossover chart after 92 weeks) had a decidedly contemporary spin. But this time, the team

that created the music for Schindler's List focuses on the greatest movie

music of all time, from the period in Hollywood known as "The Golden Age". This

music has stood the test of time, but has never been heard like this before.

Itzhak Perlman and conductor John Williams

Itzhak Perlman and John

Williams' hit recording Cinema Serenade, featuring popular contemporary

film music, has delighted audiences and critics alike. Now, the most celebrated violinist

and renowned film composer of our era have teamed up once more -- this time, with the

world-class Boston Pops Orchestra -- to serenade us with newly created arrangements of

some of the best Hollywood has ever offered.

It doesn't take much for the standard, Hollywood film score to communicate a lot of

information. Four notes from the "James Bond Theme" announce the arrival of

Agent 007, while a mere two notes from John Williams's renowned score for Jaws

let us know that the great white shark is lurking nearby. But the Hollywood music track

has also spawned more than its share of lush, well-developed melodies, some of them so

catchy that they went on to acquire a life of their own as pop songs. These "big

themes" particularly characterized what is now considered to be the "golden

age" of movie music -- scores mostly from the '30s and '40s written by such composers

as Max Steiner, Alfred Newman, and Erich Wolfgang Korngold -- and it is to this golden age

in the art of film scoring that this second Cinema Serenade recording is

devoted. In most instances, the themes -- in new arrangements created for Mr. Perlman by,

with one exception, John Williams or Angela Morley -- form a part of the ongoing

background score written for the particular films by well-established Hollywood composers.

Inspired -- and at the last possible moment -- by the discovery of a "Dear John"

letter from his (soon to be ex-) wife, David Raksin's sinuous tune Laura

quickly became a hit song, with lyrics by Johnny Mercer. In Otto Preminger's 1944 film,

however, the melody mysteriously embodies the film's heroine (Gene Tierney), who is

presumed dead throughout most of the story, which does not stop at least three men

(Clifton Webb, Dana Andrews and Vincent Price) from being obsessed with her. Mirroring

that obsession, composer Raksin never gives the theme, which shows up on both the music

track and as "source" music throughout the movie, full closure. The

sophisticated, pop-jazz quality of Laura certainly reveals the work

Raksin had done with big bands.

The 1942 Now, Voyager is one of several Warner Bros. classics (Casablanca,

also from 1942, immediately comes to mind) about an undying passion -- in this case

between Bette Davis and Paul Henreid -- whose realization is forbidden by a noble cause:

Henreid is married and has a daughter, for whom Davis will eventually become the loving

mother neither woman ever had. Max Steiner's music ingeniously mirrors the transformation

that will take place in Davis's ugly-duckling character: A fairly plain and undefinable

theme associated with Davis early in the film blossoms, with only a few alterations, into

one of the cinema's memorable love themes, as the relationship between Davis and Henreid

onboard a ship begins to warm up.

Although it was released in 1936, nine years into the sound era, about 95% of Charlie

Chaplin's Modern Times - a movie that spends much of its time satirizing

capitalism - is a silent film with a permanent score recorded onto the music track. While

the chores for writing most of the background music were handed over to David Raksin, who

was fired and later rehired by Chaplin, Chaplin himself provided many of the score's more

lyrical moments, most notably in the bittersweet song "Smile", not heard until

the very end of the film to accompany Chaplin's Little Tramp and his lady fair (Paulette

Goddard) as they walk down the road together toward what they hope will be a new life.

Writer-director Billy Wilder's 1945 The Lost Weekend, a seething portrait

of an alcoholic that won Ray Milland a best-actor Oscar (the film also garnered the award

for picture, director, and screenplay), features a dark, almost film noir score by Miklós

Rózsa, who even deploys the otherworldly sounds of the electronic theremin for the

anti-hero's major crises. The music offers few moments that would seem to qualify for

inclusion on this recording. But one of the few rays of hope in the alcoholic's life is

his woman friend, Helen (Jane Wyman), who manages - barely - to ride out the four-day

binge, and it is for the Milland/Wyman relationship that Rózsa wrote one of his typically

autumnal lyrical themes, not wholly optimistic but filled with a sad kind of warmth.

As an interlude in this concert of otherwise lyrical themes, we hear Angela Morley's

rousing arrangement of an old Irish jig, "St. Patrick's Day", also arranged in

1952 by Victor Young to help bring a happy conclusion to John Ford's The Quiet Man,

about an American (John Wayne) who returns to the Irish town where he was born, only to

find both true love (Maureen O'Hara) and, reluctantly, a good fist fight with the woman's

brother (Victor McLaglen).

The Brno-born Erich Wolfgang Korngold was steeped in a classical tradition that goes all

the way back to Mozart, with whom this Wunderkind, who was composing waltzes at the age of

seven and cantatas by the age of nine, has been compared. When his family was forced by

the rise of Hitler to leave Austria, Korngold moved to Hollywood, where his sumptuous

orchestral scores, with their dazzling but subtle instrumental and harmonic colorations,

left an indelible mark on the "Golden Age". He excelled at capturing the

swashbuckling moods and the underlying romanticism of heroic tales from the past, nowhere

more spectacularly than in the 1938 The Adventures of Robin Hood, once

described by the composer's son George as the score where Korngold "probably came the

closest to creating an opera without singing." But in the mellow love music for Robin

Hood (Errol Flynn) and Maid Marian (Olivia de Havilland), pageantry gives way to more

muted colors. This is not one of the screen's great passions but rather the natural coming

together of two kindred spirits.

Although inevitably associated with the 1942 film classic Casablanca, the

music and lyrics of "As Time Goes By" were penned by a New Jersey-born,

Tin-Pan-Alley composer named Herman Hupfeld for a 1931 stage musical called Everybody's

Welcome. In Casablanca, "As Time Goes By" becomes the

anthem of the doomed love affair between Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman to every bit

the same degree as "La Marseillaise" stands as the anthem of the film's

anti-nazi patriotism. Who can forget the moment when Bergman, deliberately rekindling the

fires between her and Bogart, tells nightclub-vaudeville-artist-turned actor Arthur

"Dooley" Wilson, "Play it, Sam. Play 'As Time Goes By' " (not

"Play it again, Sam")?

The 1944 Henry V, made in England and starring Laurence Olivier, who also

produced and directed, as Shakespeare's carouser-turned-King of England, features music by

British composer William Walton, who wrote a score filled with pageantry and pomp (the

movie starts off as a performance in the Globe Theatre), along with a stunning musical

sequence for the famous Battle of Agincourt. But the score features one hauntingly lyrical

moment, not involving the king but rather his former drinking buddies, Pistol and

Bardolph. As they prepare to leave London and join the former Prince Hal at Southampton en

route to his battle against the French, Pistol (Robert Newton) bids his wife farewell and

tells Bardolph, "Touch her soft lips, and part." (This line was modified,

probably by Olivier and/or his other two screenwriters, from Shakespeare's original

"Touch her soft mouth, and march.") Walton's soft, quiet strings, playing music

that is almost a lullaby, adds a poignant layer of pathos beneath the surfaces of these

mostly comical characters. The cue is heard here in an arrangement for violin and

orchestra by contemporary British composer Richard Rodney Bennett.

Another film theme that, like Laura, went on to become a major pop hit is

Victor Young's "Stella by Starlight", written as part of the score for The

Uninvited, an understated ghost story/mystery/romance from 1944. Young's main

theme, heard as a brief rhapsody for piano and orchestra during the title sequence, enters

the film as a song ("Stella by Starlight") composed by the story's hero (Ray

Milland) for Stella, the young woman (Gail Russell) whose mother haunts the seaside house

he and his sister (Ruth Hussey) have purchased together. Movie audiences were so taken

with the theme that Young later reworked it into a pop hit. Young, one of the most natural

melodists ever to work inside or outside of Hollywood, also came up with a hit tune in

"My Foolish Heart", which stirs up much of the romantic feeling for director

Mark Robson's 1949 film of the same title. The only movie ever to adapt a work by J.D.

Salinger (the story "Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut"), My Foolish Heart

stars Dana Andrews and Susan Hayward in yet another story of unfulfilled passion set, like

Casablanca, in World War II, although here via a flashback.

Closing this second Cinema Serenade installment are two of the greatest

romantic themes from film music's "Golden Age." There are probably few souls who

have not been stirred by Max Steiner's celebrated title theme for the 1939 Gone

With the Wind, with its heart-wrenching octave-leap upward right at the start.

Although ostensibly associated with Tara, the southern plantation where Scarlett O'Hara

(Vivien Leigh) initially lives with her family, this sweeping melody in many ways

encapsulates the entire film, from the place itself to its destruction during the Civil

War, from the selfish, headstrong young woman and her love for the selfish, headstrong

Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) to her gritty determination in the face of what appears to be

utter defeat. Almost as memorable - and also starting with an upward octave-leap - is

Alfred Newman's poignant theme for Cathy (Merle Oberon), the tragic heroine of Wuthering

Heights, an adaptation directed in 1939 by William Wyler of Emily Brontë's

nineteenth-century novel. Initially presented in the main titles, the theme in many ways

evolves with the character throughout the film until it is brutally cut short at the

moment of her death, helplessly witnessed by the forlorn Heathcliff (Laurence Olivier).

Royal S. Brown

|