Transcript

of conversation with John Williams

Star Wars music

John Williams: Another opportunity that we

have in film also is to create melodic identifications with characters. Leitmotif

technique from opera, if you like, centuries old, certainly works very well in film.

So we can identify people aurally on and off the screen. We can suggest the presence

of a character. We can sense Darth Vader's approaching, because we hear his

tune. And so these are parts of the toolbox of how we put together a soundtrack to a

film that will illicit emotions and underscore them, suggest them, enhance them.

Jaws music

Jo Reed: That was 2009 National Medal of

Arts recipient, John Williams, talking about the art of scoring films.

Welcome to Art Works, the program that goes behind the

scenes with some of the nation's great artists to explore how art works. I'm your

host, Josephine Reed. Born in 1932, John Williams has composed many of the most

famous film scores in Hollywood history, including all six Star Wars films, the first

three Harry Potter movies, and nearly all of Steven Spielberg films, notably Jaws,

Close Encounters of the Third Kind and all of the Indiana Jones movies.

Williams's also written more than a score of musical compositions for the concert hall and

from 1980 to 1993, served as the principal conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra. In

2003, John Williams wrote the composition Soundings and conducted it for the

opening of LA's Walt Disney Concert Hall. And in 2009, he composed and arranged Air

and Simple Gifts for President Barack Obama's inauguration.

I spoke to John Williams when he came to Washington DC to

receive his National Medal of Arts. We spoke in one of the dining rooms of the Four

Seasons hotel in historic Georgetown. I began our conversation with an obvious

question: 45 Academy Award nominations, 5 Academy awards, 4 Golden Globe awards, 20 Grammy

awards … do you sleep?

John Williams: Well, I sleep fairly

well. Will depend on the workload I suppose. As with all of us, the busier we

get sometimes the more spinney we become. But music is not so much of a job as it is

something we love to do. And I think, certainly in my case being now a senior

musician, anyone who's practiced music for a number of decades will always tell you, I

think, that the longer and harder we work the more we become infatuated with music and see

more in it and take more from it. And so it's hard work. Music is.

Anyone who's learned and practiced an instrument or studied to write academic fugues will

tell you it's a tough job, but the rewards are especially gratifying I think. For

me, it has been and continues to be a working life. And I think I'm lucky that my

subject is music, because it is so rewarding.

Jo Reed: Can you tell me how you

moved into composing for films?

John Williams: Well, I always

composed. As a child, I tried to write little pieces and, as a teenager, began to

orchestrate some of them. And my father was a musician, and there were theory books

sitting around the house that were there underfoot since age eight or ten or

whatever. But piano was my serious study. I hadn't intended ever to become a

professional composer. Fact wouldn't imagine anyone could earn a living doing that.

I began to work in the Hollywood studios as a pianist in the orchestras in the late

1950s. And the first appointment I had was at the Columbia Studios Orchestra. The

audition process was very simple. It was a sight-reading session. I was a

pretty good sight reader as a youngster. And I played in the orchestras of studios in

Hollywood for four or five years. Sitting every day watching older colleagues, like

Alfred Newman. Some of our listeners will remember these names. Bernard

Herrmann certainly they may remember, Franz Waxman and others. And I played for all

of these gentlemen in some fantastic films. Some Like It Hot, I played on

the piano the orchestra score of that, and actually accompanied Marilyn Monroe in the

headset when she did her little songs, and Westside Story and South Pacific,

so many of these, The Big Country, To Kill a Mockingbird. And I still

didn't have the notion that I might be a film composer or professional composer until some

of these older colleagues began to say to me can you orchestrate X scene, this is Tuesday,

we need it for Thursday morning, next Monday morning. Of course, with the temerity

of youth, when everything seems possible, we always say yes. And a very gradual

process took place, from working primarily on the piano bench in the orchestras of the

studios to the orchestrator's desk and eventually to the composing desk and was invited

then to conduct some scores of my own and of others. So it was a very gradual

process that I hadn't planned for or even anticipated that was the result of, like most

things in life, really good fortune, wonderful timing, great opportunities that came along

at about the time that I was roughly ready for them.

Jo Reed: This might be a strange

question. But can you talk about film music thinking? You compose for

concerts. You compose for films. How do you approach the music differently or

do you?

John Williams: Well, there's a

fundamental difference between film music and concert music. Film music is, very

broadly put, an accompaniment to dialog and to action. And there are rare moments

when the orchestra can take full stage. And so it would be something like examining

an opera score and taking away all the vocal parts and just having the accompaniment

played. So that when one is writing for film, one needs to bear in mind that we're

accompanying people speaking and we don't have 100 percent or 80 percent even of the

listeners' attention but we're finding a register, a tasatura, a place in the orchestra,

low, high, soft, loud, whatever, that will fit the tempo of the dialog and the register of

the dialog and the intensity of it or action and bear that in mind with every measure

we're writing. When we write for the concert hall, we assume, 100 percent of the

audience's attention or maybe 80 percent of it, we could have that much of it. And

we need to fully engage them aurally and hopefully intellectually. And when it's not

accompanying anything, it's engaging with the audience in a way that film composition

usually fails if it aspires to do. Music and film really-- you can say that there

never was silent film. When we didn't have synchronized sound, we had a pianist or a

violinist or an organist in the theater accompanying the action. And if you take

orchestral music particularly out of, let's see, example, action films and watch the film

without it, something of the energy or the circulation, if you'd like, or the temperature

of the film is taken away and it becomes inanimate almost. So the music has shown

itself to be an essential part of this audio-visual experience. And it's a very

different compositional mentality from the concert stage approach.

Jo Reed: Music for film, in some

ways also offers the audience emotional cues about how to respond to what they're seeing.

John Williams: Right. That's a

very good point. And we can not only underscore emotions that are developing but

suggest some that may not be or references or allusions to characters or feelings.

And that's a very important role in music that you point out.

Jo Reed: You're wonderful at writing

these riffs or musical signals that fit so wonderfully into the whole. You really do

create the whole tapestry. And, for example, in Close Encounters, which

has-- it's the first movie I saw where the composer got a round of applause…

John Williams: <laughs>

Jo Reed: …when the credits

rolled at the end. But that five-note tone that you did, that then was such an

integral part of the film is also part of the score that you create. Can you talk

about how you approach that?

John Williams: Well, Close

Encounters is, in my experience at least, unique. The five-note motif that you

mentioned was the result of a lot of experimentation, meeting with my friend Steven

Spielberg. I think I wrote about 300-plus examples of five notes starting with all

on one note and with no rhythmic variation, just intervallic, that is to say pitch

differences. And we settled on this one [5 Note from the film] for whatever reasons,

and it was meant to accompany the Kodaly hand signals. People may remember it was an

attempt at communication with extraterrestrials with whom we didn't know whether language

would work, whether intervallic musical sounds would work, whatever experiment that we

would do. Colors was another. We had a note for each color if you

remember. So we flashed a color and played a note to the aliens to see if they got

that and then did a combination of two or three. And finally we come to the signal

code that had certain colors to flash to it. This was a particular part of the

script that had very little to do with the underscore of the film as a whole. The

scene had to be developed musically in this way, the scene of communication. But it

then, as your question suggests, suggested to me the use of that thematic signal. It

wasn't even a theme. It was more like a signal to incorporate in the orchestral

material following that scene. Interesting to me. Five notes I always felt was

five notes as-- they all constitute a signal. You can start with the Avon doorbell,

which is, what, two notes or three? I don't know what it is.

Jo Reed: <makes two-note doorbell

sound>

John Williams: Yeah, but if you go

to seven or eight notes, it's a melody. And I kept trying to say to Mr. Spielberg,

"I need more than five notes to make this point. It isn't enough."

And his point to me was, "It should not be a melody. It should be a

signal." I think he was right in that sense that if you went a little further

you already had two bars of music that you could play in whatever mode you wanted to

express it. So it was an interesting exercise for me in getting to the point,

absolute minimal number of syllables, words, to use a literary analogy, perhaps, of saying

it all in three words instead of allowing yourself five.

Jo Reed: You have had a very long

collaboration with Steven Spielberg. How did it begin?

John Williams: We've been working

together now-- you and I are talking in 2010. Steven and I have been working for 37

years uninterruptedly. It's probably the longest collaboration <laughs> in the

history of theater or film that I know of. Gilbert and Sullivan, I don't know, with

their stormy relationship, how long that went on. I should know, but I don't.

Jo Reed: I don't think it's 37.

John Williams: I don't think

so. And I think it bespeaks a lot about Steven himself. He's a very, first of

all, very loyal man. And I can say simpatico in every way. It's been like a

marriage without disputes or arguments. We've never really had an argument.

Once in a while, we'll have not a disagreement. But I may present a scene to him

with the orchestra. He'll say might be better if you do X or Y, rarely. But

every time he's done that, when he's asked me to rewrite something, I've done

better. Rewriting actually, for me, is the art of writing anyway. To work with

the material-- in journalism, the problem always is that what we write is printed the next

day. And then a week later, if you look at the prose you've done, you think, oh, my

god, it could've been so much better…

Jo Reed: <laughs>

John Williams: …if I could've

rewritten four sentences. But you don't have that opportunity. And writing

film music is similar to journalism in that we record the score. The next day it's

being dubbed. That is mixed. The soundtrack's being permanently fixed, and

it's out before the public. And you may hear it six months later and think, oh, I

could've done so much better if I'd had another month on that. But that's part of

the-- one of the dynamics of commercial filmmaking.

Jo Reed: Do you compose after you

see a cut of the film?

John Williams: Yeah, the cut of the film

will give us a lot of things, tempo, rhythm, length of things, dynamics of all

kinds. It'll even suggest textures, timbres, the coloration of-- many things that we

mustn't do here and things that are required that seem to be necessary. There are

some exceptions. You and I talked about Close Encounters a few moments ago

and the signals scene, the five notes. That musical shootout between the computer

board and the arriving ETs was prerecorded before the scene was shot, because we needed to

have the music to shoot the scene to. There are other examples I could give you.

Occasionally a director will come and say here's a scene that I want to do and it will do

X or Y. Oh, another more recent example, Harry Potter, Hedwig's music, the owl that

flies and has his music. Warner Bros. said can you create some music to which we

will manufacture a trailer that we can create to that music. And so I wrote and

recorded the music with the orchestra. Warner Bros. put together their trailer

advert film for the first Harry Potter film. And everyone seemed to like the

piece. So it became the main theme of most of the films. And that was written

before I saw any film. I'd read the book and had an idea of what Harry Potter was, I

thought, going to be musically I thought. So in answer to your question, 95 percent

of the cases in film music, we all want to see the film first. But there are notable

exceptions.

Jo Reed: You wrote all the scores

for the Star Wars films. The difference between the first one and the

last-- the sequel, in some ways, has to-- there are musical references. But at the

same time, you're also composing anew. Can you talk about that juggling act a bit?

John Williams: Well, the Star

Wars experience has been, I think, unique in music history, film music history.

Not because of me, there's no waving my own flag, but because of this simple reason.

The first Star Wars film that I did with George Lucas, whenever that was, I had

no idea they were going to be-- he didn't tell me there was going to be a second, Empire

Strikes Back. I never heard of such a thing. And I thought that Star Wars

was just over and completed when I put the baton down the end of the first

recording. And a year or so later, he rang up and said, "I have the next

installment. And we need the old music from the first film, but we also need new

music for new characters, new situations." So a process started, that lasted

over, I guess, 20-plus years, of adding bits and pieces of material to a musical tapestry

that started to become-- started to pile up off the floors, quite a extensive library of

music. Each film having over two hour's of music. So there's about 12 to 14

hours, maybe 15 hours of orchestral music composed over a period of not 2 years but

20. And that, I think, is a unique opportunity for a composer, one that I never

expected to have. And it gave me an opportunity to do the things we talked about a

few moments ago that I hadn't otherwise had. That is to say an opportunity to go

back over and perhaps improve some of the things I'd done. And what's fascinating

is, to me, that maybe some of the newer music isn't any better or as good as the earlier

ones. That's one's own personal inner struggle, inner voice. When you write

something when you're 40 years old, you wouldn't write it the same way when one is 70 and

vice versa. One may be better than the other or a different kind of energy or

different kind of acuity, whatever will go with it. So it's been a fascinating

journey, Star Wars.

<crew talk>

Jo Reed: It's hard to think of music

that announced a film with more verve than your music did for Star Wars.

The music helped make it an event. You hear the music, and everybody just lights up

right away.

John Williams: Fantastic

opportunity. I did see the credit crawl. I can't quote you what's on it.

I should be able to I suppose. I love that.

Jo Reed: Long ago and far away…

John Williams: Looking at that

thing, I thought, well, it has to be a grand fanfare and it has to start off with, put it

this way, with a bang, with a full fortissimo explosion of energy and trumpets and the

rest of it. And so I wrote the piece that I wrote. It starts with an unprepared,

high C on the trumpet. People can hear the music itself. The way that

orchestra-- there's no preparation note for the trumpeters. It's very

difficult. They have to grab it right out of the ether. It was a particularly great

performance of brass playing. And so the spirit of, I think you could also say, militarism

of the British brass tradition is apparent in the performance I think, in the writing

also. Because it is a military piece after all, spaceships and an army of space, if

you like to think of it that way. So it has that swagger and that sense of

commitment and dedication to the journey.

Jo Reed: I read, and correct me if

I'm wrong, that Joseph Campbell had something to do with the way you envisioned the

film. Is that true?

John Williams: Well,

belatedly. He instructed all of us I guess. After the first film appeared, he

did his now famous interviews about Star Wars and, of course, told all of us,

those of us doing the film, probably even George Lucas who created it, I think they were

fascinated with each other, he pointed out to us that these connective links with

mythology and shared memory even across cultures added force to the nostalgia and the

revived recollections of past heroes, if you like, and all the villains and so on was some

sort of fundamental part of our humanity and explained to us that what we thought was

going to be a Saturday morning popcorn picture for kids, which I thought it would be at

the least, was something that resonated with people around the world. You expect it

to be a children's film, but it does so much more for all the reasons that Joseph Campbell

was able to articulate to us. I'm sure he's right. And the resonance of the

music also I think is part of that awakening that takes place in our psyches, in this

cross-generational <laughs> wave of neurons that go through all of us, from

generation to generation, where we remember things. And we clearly do. They're

not our experience, but they're the experience of our collected past, Star Wars.

Jo Reed: And there's something about

music that just, I think, allows people to apprehend that on such a deep level. You

know it almost without knowing.

John Williams: It is

fascinating. Leonard Bernstein spent his whole life, I think, trying to teach us

that music is one thing. And, sure, there's great diversity in music, but there are

universals in music that don't exist in language. Noam Chomsky and others will try

to find them, and they get a grunt or a syllable shared by all the cultures. But,

the music, that's divided in nature. A string is a string and it divides in half in

an octave whether you're in Tibet or you're in New York City. So it's a shared

language with our physiologies. It's part of how the ear works and the brain

measures and the balance is attained in …

Jo Reed: It resonates inside.

John Williams: And resonates inside

emotionally. So we use music for our birth and for our wedding and for our death and

for our celebrations and for our wars and for our victories. And we don't

understand. Least I don't. I don't think Bernstein ever articulated it.

No one could do better than he. It is part of our humanity. We need it like we

need to share language in the same way. And that's why it's so important that it's

taught. Children who study music learn a different metric system. They learn

to calculate things aurally, intervals and so on, do, re, mi's, giving special kind of

instruction to the brain. And performance is a way of setting aside individuality.

You sit in an orchestra, join a chorus. You cease to become an individual. Now

you're part of a unit that performs in a very special way. So music performance is

an important part of social interaction. Yeah, music is like breathing. Have a

cliché. It's an important part of our human experience.

Jo Reed: Well, we mentioned earlier

your compositions for concerts. And you inaugurated the new Disney Hall in Los

Angeles, and you also did an arrangement of Air and Simple Gifts for the

inauguration. Talk about that.

John Williams: The opportunity to

participate in the inauguration of President Obama was certainly a special, great event in

my life experience. The President very wisely selected Yo Yo Ma to play. The president

asked Yo-Yo if he would put together a small group, three or four musicians only, to play

something that would be four to five minutes long. And that Yo-Yo could select his

colleagues, and he did. He selected fantastic group of musicians and rang me up and

asked me if I could either write a piece, organize something that might be appropriate for

that moment. Either the president told him himself or he heard that the president

was particularly fond of Aaron Copland's music. And, of course, there's no Copland

music for that combination of instruments in Copland's pretty vast canon. And what

we know of Copland--most people, American audiences, will think of Appalachian Spring,

the famous ballad that Copland wrote. Some of which has the wonderful old Shaker

hymn Gift Be Simple in it. So I thought a combination of the Shaker Air, as

a tribute to President Obama's affection for Aaron Copland, might be appropriate if I

could combine it with some perhaps slightly hymnal idea that might express, in a very

simple and not ostentatious way, the solemnity and beauty of the moment and the promise of

the moment and put it together for actually a kind of esoteric combination of instruments,

violin, cello, piano and clarinet

Air and Simple Gifts…

John Williams: So that was the

result of this effort. And it brought me together with two of my favorite

colleagues, Yo-Yo Ma and Itzhak Perlman, and two younger people that I hadn't known before

that Yo-Yo selected.

Jo Reed: Anthony McGuill and Gabriela

Montero

John Williams: And we were allowed

the great once-in-a-lifetime privilege of participating in that event.

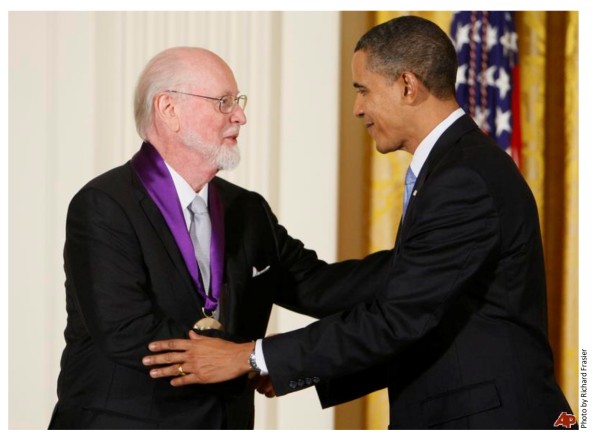

Jo Reed: You have won many awards and now

the National Medal of Arts, which is the highest award the nation gives to an

artist. Can you just tell me what you thought when you won that award?

John Williams: Well, I'm still a

little bit numb about it, because it is so grand. And one can only think could

anybody ever be deserving of such an honor. There's so many people who we could name

that would be deserving. And I just feel, beyond being a little bit stunned about

it, frankly, enormously grateful and very excited about it. And I think what it does

for me is want me to be better, and I hope I have time to do that.

Jo Reed: And I join you in that

hope.

John Williams: <laughs>

Jo Reed: Thank you so much, John

Williams. It was really a pleasure and a well-deserved honor. Thank you.

John Williams: Thank you.

Jo Reed: That was National Medal of

arts recipient john Williams talking about his extraordinary career as a composer.

You've been listening to Art Works, produced at the

National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor.

Excerpts from the soundtracks to E.T. and JAWS used,

courtesy of Universal Pictures. Excerpts from Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back, used

courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment. Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind,

from the CD The Music of John Williams used courtesy of Silva Screen Records. Excerpts

from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, used courtesy of Warner Brothers. Excerpts

from "Air and Simple Gifts," performed by Yo-Yo Ma, Itzhak Perlman, Gabriela

Montero and Anthony McGill, used courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.

All the music has been composed and conducted by John

Williams.

Thanks to the Four Seasons Hotel in Washington, DC.