Track Listing

1. 20th Century Fox Fanfare / Main

Title, The Imperial Probe (05:45)

2. Luke's First Crash (02:29)

3. Han Solo and the Princess (04:24)

4. The Asteroid Field (04:12)

5. The Training of a Jedi Knight and "May the Force Be With You" (01:55)

6. The Battle in the Snow (03:02)

7. The Imperial March (03:20)

8. The Magic Tree (03:37)

9. Yoda's Theme (03:33)

10. The Rebels Escape Again (03:01)

11. Lando's Palace, The Duel (Through the Window) (05:02)

12. Finale (04:35)

John Williams and His

Music

(Liner Notes from the 1997 release)

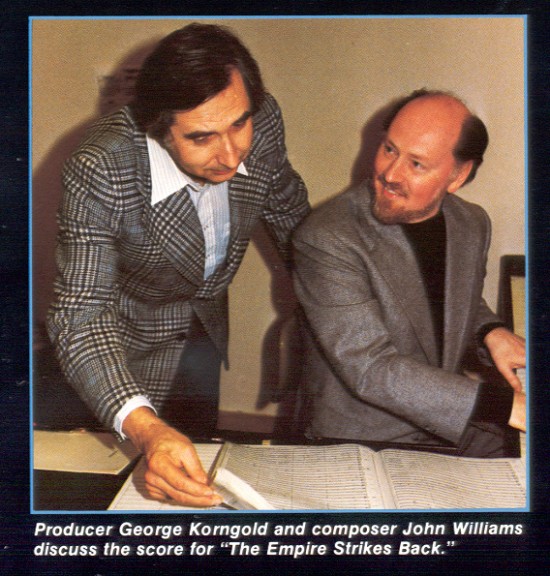

John Williams. born in New

York in 1932. seemed destined at first to be a pianist rather than a composer. He studied

at Juilliard under Rosina Lhevinne, and his early years in Hollywood were spent playing

piano in studio orchestras. At this time – the mid·1950s – Hollywood was still

in its heydav, and Williams found himself working for composers of the caliber of Alfred

Newman. Franz Waxman and Dimitri Tiomkin – the best possible practical experience for

one destined later to step into their shoes. At UCLA Williams studied composition with

Mário Caslelnuovo-Tedesco, and his latent ability as writer was soon recognized in the

studios. At first he wrote only orchestrations (Adolph Deutsch's The Apartment and

Tiomkin’s Guns of Navarone) were among the films he worked on in this capacity) and

he acknowledges a great debt in this regard to the late Conrad Salinger, then the man

responsible more than anyone else for the unique sound of the MGM musicals. Something of

Salinger’s influence perhaps survives, specifically in the extraordinarily beautiful

end-title orchestral setting of the Superman love-theme and. in more general terms. in

Williams' work as arranger/musical supervisor on such musicals as Goodbye Mr. Chips.

Fiddler on the Roof and Tom Sawyer. To these productions he brought style and fine finish

in a manner redolent of the good old MGM days at their best.

By the early 1960s Williams

was composing music for feature films and TV, producing between 15 and 30 minutes of music

per week, often for months at a stretch. for the Kraft Theatre series. He also worked for

Columbia Records' as pianist. arranger and conductor, and made a number of albums with

Andre Previn. who was under contract at the same time. Films tended to be glossy comedies

like John Goldfarb Please Come Home and How To Steal A Million, but took a more serious

turn in the early 19705. Major directors began to look in his direction, chief among them

Hitchcock (Family Plol) and he almost became typecast as a disaster-movie specialist

(Earthquake, The Poseidon Adventure, The Towering Inferno). Other important scores of the

early to mid-1970s include The Reivers, Images, The Cowboys and The Missouri Breaks. His

association with Steven Spielberg began with Jaws in 1976 and has so far encompassed also

the masterly Close Encounters of the Third Kind and 1941. Star Wars was a milestone not

only as far as Williams' career in itself was concerned but also because it marked the

re-emergence into the limelight and critical approbation of the symphonic film-score,

dormant for nearly a decade. The Fury. Superman and Dracula followed in quick succession,

to the more current Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T., Return of the Jedi. and Indiana Jones

and the Temple of Doom.

Williams has never cared to

become stigmatized as a composer exclusively for movies: therefore. he has maintained also

a steady flow of concert works written for the most part in an advanced but still

basically tonal and expressive idiom. His Essay for Strings has been widely played in the

USA, his Sinfonietta for wind ensemble was recorded by DGG. and his Symphony No.1 received

an important London performance under André: Previn. A recording of the Williams Violin

and Flute Concertos (Varese Sarabande Digital 704.1201) was released in 1983. In 1980 he

succeeded the late Arthur Fiedler as conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra.

John WiIliams is a complete

professional in respect to every facet of his art. He is not a man to indulge in

egomaniacal braggadocio or publicity-seeking gimmickry: rather he is a private person,

quiet reserved (though never aloof), soft-spoken (though very articulate in the matter of

expounding his technique and thought-processes), and an oasis of cool, commanding

competence in a business constantly and frenetically riven by practical pressures and

clashes of artistic temperament. His approach is a no-nonsense, down-Io-business one with

respect not only to the writing of his music but to its performance and recording: one can

well imagine him earning the esteem of the late Benjamin Britten whose work and life-stvle

similarly bore all the marks of a supreme and well-ordered professionalism. In fact

Williams perpetuates the tradition of Hollywood studio craftsmen in whose midst he grew

up, men who gave no thought to the wearing of posterity as an armband but who were

concerned merely with doing there job to the best of their ability and with a minimum of

fuss and bother. When as in Williams' case, this deceptive ease in the negotiating of

intimidating: technicalities and practicalities of filmscoring is combined with what may

appropriately be described as 'star quality' in a composer, the resulting draught has to

be a heady one.

Williams produces his music as

required and on time and in vast quantities. His composing method is identical with

Prokofiev’s inasmuch as the music is first laid out In the form of very detailed

sketch or compressed score: this is then turned over to a skilled and long trusted

colleague for the preparing of a full orchestral score. In this way the composer is spared

a deal of time and physical energy which he can then focus far more profitably on the

actual substance, the musical quality, of what he is composing. And the consistent quality

of Williams music in the light of his high productivity rate compels admiration. This has

become the more noticeable over the last few years inasmuch with the advent of Star Wars

his musical personality seemed to take on a sudden and vivid new dimension. His

instrumental expertise had never been in question, but Star Wars revealed a new access of

technical power. an enhanced splendour and luxuriance of orchestral imagination. The same

film brought evidence of a new strength and distinction of melodic invention, an

impression consolidated by the finale of Close Encounters, Superman and The Empire Slrikes

Back. The latter yielded a fine crop of tunes. The romantic theme for Han Solo and the

Princess is shot through with a quality of intergalactic remoteness which finds a perfect

foil in the warm expressiveness of Yoda’s Theme, first cousin to the Superman

love-theme (surely Williams loveliest Iyrical inspiration to date). But the piece de

resistance of the score is the Imperial March, tart, rhythmic and aggressive: a fine

contrast to The Throne Room in Star Wars which was another Imperial March but of the

Elgarian, pomp-and-circumstantial order. Williams, in fact, almost alone among the new

generation of film composers, has developed a sense of the epic: he can write in the grand

manner, paint with broad strokes on a wide canvas. and do it with conviction. He has

acknowledged his need to adopt musical styles in order to supply the needs of films widely

divergent in character. He has also stated his belief that making the sound of

today’s films relevant to the films themselves involves borrowing elememts, without

prejudice. from whatever musical disciplines and traditions suit the purpose. He likes the

idea of the blending and coalescing of traditional notions of musical syntax and

expression with avant-garde techniques and pop, but is not interested in machine-made

music: in the case of Robert Altman's Images all the human or subhuman effects were

produced by live performers. At heart, Williams is a romantic traditionalist; the score of

Close Encounters progresses with irrefutable dramatic, emotional and musical logic from a

black chaos of atonality to a pure transfigured E-major diatony at the climax and

consummation, and asserts the relevance of tradition to the world of today and tomorrow.

One is reminded of the late Bernard Herrmann’s prophecy that the music of the future

would move toward a new clarity and simplicity.

In an age when many

contemporary ‘concert’ composers have completely lost touch with their public,

no one should underestimate the power of the cinema as a world-wide transmitting network:

it cultivates musical awareness and determines mass-audience taste to a much greater

extent than is commonly realized. Williams and his colleagues active in films –

Miklos Rózsa, Jerry Goldsmith, Elmer Bernstein and Leonard Rosenman among them – are

obliged to maintain civilized contact with their listeners, otherwise the effect of their

work would be negated. But in maintaining this contact they are continually finding new.

vital and exciting things to say – things people want to hear within the confines of

an idiom which in theory has been obsolete for decades. In practice it has never been more

alive. The Empire Strikes Back and other scores of its genre bear triumphant testimony to

that.

Christopher Palmer

London. England

|