Track Listing

JOHN WILLIAMS (*1932)

THE FIVE SACRED TREES

(Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra)

1. I. Eo Mugna (6:54)

2. II. Tortan (3:53)

3. III. Eo Rossa (4:06)

4. IV. Craeb Uisnig (2:53)

5. V. Dathi (8:01)

JUDITH LeCLAIR, BASSOON

TOTU TAKEMITSU (1939-1996)

6. TREE LINE (9:52)

ALAN HOVHANESS (*1911)

SYMPHONY NO. 2 OP. 132

"MYSTERIOUS MOUNTAIN"

7. Andante con moto (5:12)

8. Double Fugue (Moderato maestoso, allegro vivo) (6:04)

9. Andante espressivo (5:20)

TOBIAS PICKER (*1954)

10. OLD AND LOST RIVERS (4:44)

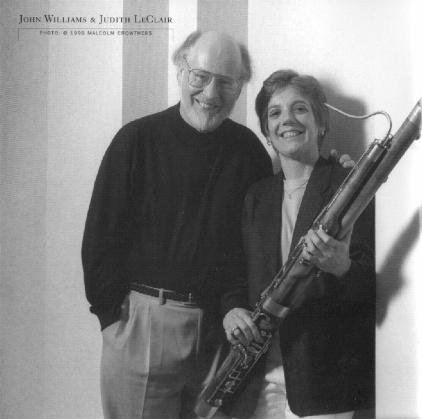

John Williams and Judith LeClair

As we become increasingly aware of the damage

done by the destruction of our forests, it is illuminating to discover that our ancestors,

many thousands of years ago, prayed to the spirits before felling a tree. One prayer was

appropriate for a maple, another for the elm, the ash, and so on.

The English poet, Robert Graves, writes of these prayers, which I have been unable to

find, but which nonetheless, have moved me to compose this music featuring the bassoon,

itself a tree.

This is all the result of a request for a concerto by the great bassoonist Judith LeClair,

whose unparalleled artistry is a mystery and a wonder in itself.

I

Eó Mugna, the great oak, whose roots extend to Connia's Well in the

“otherworld,” stands guard over what is the source of the River Shannon amd the

font of all wisdom. The well is probably the source of all music, too. The inspiration for

this movement is the Irish Uillean pipe, a distant anscestor of the bassoon, whose music

evokes the spirit of Mugna and the sacred well.

II

Tortan is a tree that has been associated with witches and as a result, the fiddle

appears, sawing away, as it is conjoined with the music of the bassoon. The Irish Bodhrán

drum assists.

III

The Tree of Ross (or Eó Rosa) is a yew, and although the yew is often referred to as a

symbol of death and destruction, The Tree of Ross is often the subject of much

rhapsodizing in the literature. It is referred to as "a mother's good,"

"Diadem of the Angels" and "faggot of the sages". Hence the lyrical

character of this movement, wherein the bassoon oncants and is accompanied by the harp!

IV

Craeb Uisnig is an ash and has been described by Robert Graves as a source of strife.

Thus, a ghostly battle, where all that is heard as the phantoms struggle, is the snapping

of twigs on the forest floor.

V

Dathi, which purportedly exercised authority over the Poets, and was the last tree to

fall, is the subject for the close of the piece. The bassoon soliloquizes as it ponders

the secrets of the Trees.

John Williams

Liner Notes

Somewhere in a forgotten land and a forgotten

time, the wind mingled with the leaves of sacred trees. Dumbfounded by a melodious sound,

humankind paused in amazement to listen. Out of silence music was born.

There are many different tales about the magic

and majesty of trees-stories more ancient than our longest memories. In the legends of

almost every culture there is a sacred tree standing at the center of the world. In the

dawn of the Near Eastern cosmos the tree of Eden stood at the heart of paradise. At the

center of the world of the ancient Maya there was another sacred tree called the ceiba.

And on the African veldt there are other sacred trees, standing alone and knurled in the

midst of dusty villages. Even in the lore of pre-Christian Europe, there arc many Celtic

legends about a grove of five sacred trees. In every hallowed land there are still holy

people who sit beneath wind-blown branches. They are the prophets, the soothsayers, and

the storytellers of their people. In the shadow of the sacred trees they tell the tales of

their tribes, stones that flow from generation to generarion like a vase and ancient

river. The enure history of humankind resounds with the miraculous music of wind among the

branches of sacred trees.

Composer John Williams has heard this rustling

music of the leaves. Startled into his own awakening by stories about the mythic Five

Sacred Trees, he created an exceptional musical tapestry for orchestra and bassoon, an

instrument that Williams believes is "haunted" by the spirit of the tree from

which it is made. His music reflects the composer's profound veneration of the forest.

"Within the tree community," he tells us, "there lies more music than

anywhere else in the Western world. It is impossible to stand under the high arching

boughs of ancient trees and not wonder if [he architecture of cathedrals was not born of

just such an experience."

The Five Sacred trees, in the form of a

Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra, consists ot five contrasting movements that eloquently

evoke each of the legendary trees of Celtic myth: Eň Mugna. a symbol of the Sturdy oak,

begins with solo bassoon, a deep throated voice that lends a somewhat solemn mood to this

lyrical homage to the enduring oak. Tortan is John Williams' tribute to the mythic tree

associated with witchcraft, which he interprets with a spritely dance tune for fiddle and

bassoon, Eň Rossa, or the Tree of Ross-the yew, which summons the rhapsodic powers of

destruction and recreation, begins with a delicate theme for solo harp followed by a long,

lean line for bassoon over harp accompaniment. Craeb Uisnig, the Celtic name for the ash,

a tree that is often a symbol of strafe, brings on an agitated theme, punctuated by drum

beats, glissandos, and a rousing series of plucked rhythms in the strings. Finally, there

is Dathi, a tree that is The muse of poets and, significantly, is also the last tree to

fall in the legendary Forest of Celtic mythology, expressed as a lyrical, somewhat,

melancholy duet for bassoon and flute.

John Williams has created a work of great

lucidity, marked by the radiant clarity of chamber music-a lacework of delicate melodies

that transcend the prosaic world and invite the listener to experience that strange,

illusive music that can be heard only amidst the community of trees that still survives in

the deepest forest.

Composer Williams discovered the tales of The

Five Sacred Trees in the writings of the British poet and mythologist Robert Graves, whose

landmark studies of pre-Christian lore and religion celebrate the primordial rites that

joined the everlasting and ominous powers of nature with the fragile lives of humankind.

In Graves' writings, John Williams found descriptions of prehistoric Celtic rituals that

demonstrated a reverence for nature that has become increasingly rare in industrial

nations. Among the ancient Celts, it was necessary to recite a specific prayer Before

felting a tree-a ritual reminiscent of the lore of many other primal peoples, like Native

Americans who recited prayers and wept before killing any creature.

John Williams' The Five Sacred Trees was

commissioned in 1995 by the New York Philharmonic in celebration of its 150th anniversary.

A brilliant performance by bassoonist Judith LeClair lends a mysterious and lyrical

intimacy to this premiere recording by the London Symphony Orchestra.

From the outset of his musical career,

composer Toru Takemitsu reflected the unique veneration of nature that is

an intrinsic part of Japanese culture-visible in the poetic immediacy and sensuality of

poets like Bosho and painters of minimalist Zen landscapes such as Tawaraya Sotatsu. Even

today, when the influence of the West is virtually inescapable, the people of Japan do not

have to discover their kinship with nature by searching into a forgotten past. In fact,

their acquaintance with the natural world is something of an obsession. Takemitsu has

carried this Japanese tradition of nature worship into twenti-eth-century music, creating

a repertory of highly transparent and evocative tonal experiences in which color and

light, rather than musical line, provide a uniquely poetic musical idiom. In this way,

Takemitsu perpetuates the cosmic vision; of Japan at the same time that he mingles Eastern

and Western influences due, at least in parr, to his strong affinity for the music of

Claude Debussy, whose colorist compositions were, ironically, greatly influenced by Asian

music. Tree Line, composed in 1988, is a perfect representation of Takemitsu's musical

voice. As the composer explained, the tree line of the title refers to a row of acacia

trees that stood near the mountain villa that served as his workshop. Takemitsu composed

the work as an homage to the dauntless serenity of the trees and their power to inspire an

overwhelming sense of time and endurance. For, as the composer noted in a collection of

essays (From the Space Left in Music), trees symbolize the visualization of time through

their annual rings that are always subtly different, year by year, marking the silent

passage of time. Tree Line is a perfect miniature, delicately spinning, note by note, its

own vision of time as an element of sound.

The highly layered and luminous music of Alan

Hovhaness, with its distinctive Armenian and Far Eastern flavor, is a singular

example of composition wrought in the isolation of the West Coast, far from the influences

of main-stream musical life. Composed in 1955, Symphony No 2, "Mysterious

Mountain," was strikingly ahead of its time, having far more in common with the

visionary compositions of late twentieth-century composers like Arvo Part and Henryk

Gňrecki than the nationalistic works of Hovhaness' American contemporaries, Virgil

Thomson and Aaron Copland. By far the most popular of the repertory composed by Hovhaness,

"Mysterious Mountain" recalls the so-called "painters of the

sublime"-those American painters of the nineteenth century, such as Thomas Moran and

Albert Bierstadt of the Hudson River School-whose passionate images of unbounded

landscapes expressed an American idealism and mystique, an envisioning of a nature that is

far larger than life. Like those painters, he uses a massive canvas, a fervently romantic

brush stroke, and the inspiration of a greatly outsized natural world devoid of human

presence. "I named the symphony," Hovhaness explained, "for the mysterious

feeling chat one has in the mountains-not for any special mountain, but for the whole idea

of mountains."

For all of its unlimited industrialization,

the United States has retained a keen delight in the out-of-doors which is, doubtlessly,

one of the reasons Europeans are somewhat perplexed by the persistent American tradition

of setting aside precious land as national parks rather than creating more industrial

parks, And, yet, the paradox of American industrialism and American conservationism is

doubtlessly symbolic of a unique sensibility found in the United States. Composer Tobias

Picker reflects this American paradox, in his propulsive and urbane works that

contrast markedly with his highly romantic and nostalgic pieces like Old and Lost Rivers

(1986). This native of New York City comfortably straddles two worlds: an internationalism

that is rarified and highly cosmopolitan, and, on the other hand, a far more intimate and

personal affinity with the natural world that conveys an accessible and romantic spirit.

Old and Lost Rivers was one of a series of works created by a group of renowned composers

for the "Fanfare Project"-short pieces commissioned by the Houston Symphony in

celebration of the Texas Sesquicentenmal year (1986). Many of the composers invited to

participate in the Project-conceived by Tobias Picker, then Composer-in-Residence of the

Houston Symphony - inevitably wrote rather grandiose fanfares, but Picker himself decided

to compose a piece that is marvelously tranquil. As Picker explains, the name Old and Lost

Rivers derives from a natural phenomenon-the network of bayous that lie east of Houston

near the vast Trinity River, which snakes down from Dallas to the Gulf of Mexico. The

bayous arc traces of the Trinity River that have been left on the land when the great

river has shifted from time to time. In this way, the bayous are ghost rivers, curling

lazily over the landscape-green and bird-filled when the weather is dry, and full of

sluggish- brown water during the rainy season. The two main bayous are called Old River

and Lost River. Where they converge, there is a sign that reads: Old and Lost Rivers.

All the music of this album is dedicated to a

celebration of the world of nature that lies beyond human frailty. It is music that denies

the Western idea that nature is only a resource rather than an integral part of our lives.

The composers of this music represent a small group of visionaries, who evoke the drama of

the world rather than the drama of ourselves, and who have created a different kind of

musical sensibility, one that is shamelessly melodic and profoundly touching.

Jamake Highwater

|