Track Listing

1. JOHN WILLIAMS (b. 1932): Summon the Heroes

- Short Version (for Tim Morrison) (3:39)

(Written for the Centennial Celebration of the Modern Olympic Games,

Atlanta, Georgia, July 19, 1996)

FIRST RECORDING

2. CARL ORFF (1895-1982): O Fortuna* from

"Carmina Burana" (2:39)

3. LEO ARNAUD (1904-1991) and John Williams: Bugler's Dream/Olympic Fanfare

and Theme (4:31)

(“Bugler's Dream” introduced during the 1968 Olympic Games,

Grenoble)

(“Olympic Fanfare and Theme” written for the 1984 Olympic

Games, Los Angeles)

4. MIKIS THEODORAKIS (b. 1925): Ode to Zeus* from

"Canto Olympico" (3:42)

(Commissioned By The International Olympic Committee For The 1992

Olympic Games, Barcelona)

5. MICHAEL TORKE (b. 1961): Javelin (8:53)

(Commissioned by the Atlanta Committee for the 1996 Olympic Games

Cultural Olympiad

in celebration of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra's 50th

Anniversary)

6. LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918-1990): Olympic Hymn*

(5:22)

(Written for the 1981 International Olympic Congress, Baden-Baden)

Text: Günter Kunert

FIRST RECORDING

7. JOHN WILLIAMS: The Olympic Spirit (4:06)

(Written especially for the NBC Sports Division in celebration of the

1988 Olympics, Seoul)

FIRST RECORDING

8. VANGELIS (b. 1943): Conquest of Paradise (Theme)*

(3:38)

9. DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975): Festive

Overture, Op. 96 (6:19)

(Theme of the 1980 Olympic Games, Moscow)

10. JOSEF SUK (1874-1935): Toward a New Life (5:54)

(Silver medal-winning composition at the 1932 Olympic Games, Los

Angeles)

11. MIKLÓS RÓZSA (1907-1995): Parade of Charioteers from

"Ben Hur" (3:49)

12. VANGELIS: Chariots of Fire (Theme) (3:38)

Randy Kerber, Synthesizer

(Featured in the 1981 Academy Award-winning film

and performed at the 1984 Olympic Games, Sarajevo)

13. JOHN WILLIAMS (b. 1932): Summon the Heroes - Full Version

(for Tim Morrison) (6:17)

* Tanglewood Festival Chorus

John Oliver, Director

Liner Notes

“THE IMPORTANT THING IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES

IS NOT TO WIN BUT TO TAKE PART; THE IMPORTANT THING IN LIFE IS NOT THE TRIUMPH BUT THE

STRUGGLE. THE ESSENTIAL THING IS NOT TO HAVE CONQUERED BUT TO HAVE FOUGHT WELL. TO SPREAD

THESE PRECEPTS IS TO BUILD UP A STRONGER AND MORE VALIANT AND, ABOVE ALL, MORE SCRUPULOUS

AND GENEROUS HUMANITY.”

BARON PIERRE DE COUBERTIN,

FOUNDER OF THE MODERN OLYMPIC GAMES

John Williams (1996)

There is a moment toward the end of Homer's Iliad (Book XXIII) when the Achaeans, after

defeating Hector and the Trojans, attend to the burial of their own hero, Patroclus. It is

a solemn affair, with much weeping and heartache. But after they have burned Patroclus on

his funeral pyre, gathered his bones in a golden jar “with a double fold of

fat,” and entombed him in a grave mound, a curious thing happens: as the Achaeans

prepare to leave, Achilles, their leader, calls upon his warriors to join in a series of

games — chariot races, boxing, wrestling, foot races, dueling, shot-putting, archery

and spear-throwing. Achilles, as patron of the games, will donate all the prizes —

among them, cauldrons and tripods, “a woman faultless in the work of her hands,”

a six-year-old unbroken mare carrying a mule foal, and gold. But the quality of the prize

is of little importance to the participants in these games: the real purpose of victory is

glory, to be remembered in tales like the Iliad as the rider, boxer, or wrestler who won

the games commemorating Patroclus, the fallen hero of the Achaeans.

When, at the end of the nineteenth century, Baron Pierre de Coubertin conceived of

instituting the modern Olympic Games, he was undoubtedly inspired by Homer's tale and

similar ancient epics that described in wondrous detail the mythic entanglements of

mortals and divines. The baron was not alone in his fascination with ancient culture.

After conquering the planet with science and industry, Victorians as a whole had become

intrigued with matters spiritual, mythical, and supernatural — Sir James Frazer's

Golden Bough (“a study of magic and religion,” the subtitle tells us) was

extraordinarily popular in its day, though it was of encyclopedic proportions and global

in its coverage.

Indeed, there was a movement afoot — among certain classes of anthropologist and

folklorist, at least — to find the common root of all peoples. The Grimm brothers,

Jakob And Wilhelm, had started it all back in the early nineteenth century, not so much

with their celebrated collection of wonder tales as with their histories of grammar and

language and their efforts to discover the source of the Indo-European language family;

others had gone so far as to compile massive catalogues of myths, tales, and narratives

that were subsequently broken down and analyzed to reveal the essential oneness of our

storytelling traditions.

Some of it was folly — wild speculation, in many cases — but some of the ideas

that came out of these Victorian pipe dreams proved to be unusually good, particularly

regarding the civilization of ancient Greece, which was the culture these armchair

anthropologists knew best. The Classicists paid particular attention to the

interconnectedness between expression and endeavor in the Hellenic world and the peculiar

relation of these human occupations to the world of the gods. Just as the arts in the

Hellenic world had largely been acts of religious devotion — or so our Victorian

ancestors thought — their literature suggested that games, such as those held by the

Achaeans at the funeral of Patroclus in Homer's Iliad, were also acts of tribute, be it to

a fallen hero or a powerful deity.

In founding the modern Olympic Games the Baron de Coubertin sought a renewal of the idea

that both the Artist and the Athlete were intermediaries between the heavens and earth, as

well as a rediscovery of the dedication and devotion that made such mediation possible. In

that sense, like Homer's Iliad, the Baron's vision of the Olympic Games and his

short-lived effort to incorporate arts competitions as part of the games were at once

metaphorical gesture and emblematic act. The metaphorical gesture linked athletic and

artistic performance with the human spirit — that part in all of us that eschews

personal gain in favor of a greater good. And there, in the metaphor, we also find the

emblem: the athlete straining to achieve what has never been achieved before, nevertheless

just as human as the rest of us.

In the century since the renewal of the Olympic Games, much has changed in the games

themselves — the inclusion of team sports, for example, and even the injection of

patriotic chauvinism. Yet the baron's vision still holds true: the Olympic Games, in their

presentation of the individual's struggle with the limitations of one's very humanity,

provide us all with models for the conduct of our daily lives.

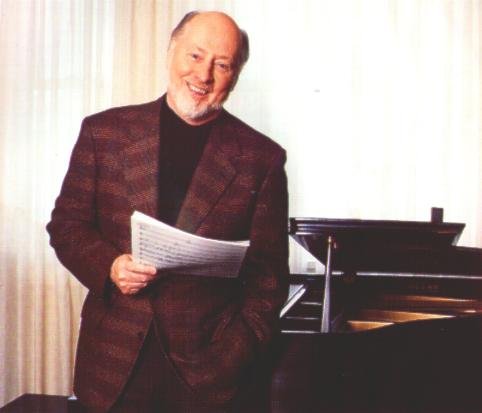

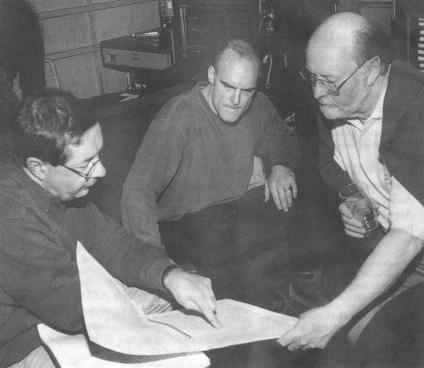

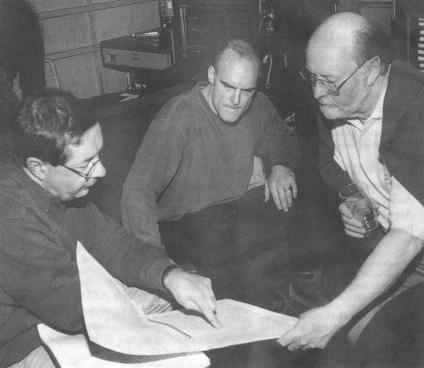

Shawn Murphy, Tim Morrison (Solo Trumpet), John

Williams

“I remember seeing a photograph of a

female athlete suspended above the ground, every fiber of her being stretching for a ball

just beyond her reach ... captured in a shot, freezing time and denying gravity. There is

unquestionably a spiritual, non-corporeal aspect to an athletic quest such as this that

brings us close to what art is all about.”

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games one hundred years ago,

would have approved of John Williams' words, above, which echo his own: “Sport must

be seen as producing beauty and as an opportunity for beauty. It provides beauty because

it creates the athlete, who is a living sculpture. It is an opportunity for beauty through

the architecture, the spectacles, and the celebrations which it brings about.”

This recording, featuring works by Williams, Leo Arnaud, Carl Orff, Leonard Bernstein,

Dmitri Shostakovich, and others, certainly counts among the Baron's “opportunities

for beauty.” Some of the works come from the Games themselves—Josef Suk's

“Toward a New Life,” indeed, won a silver medal in the 1932 Olympics for musical

composition—others from what might loosely be called the “spectacle”

inspired by the Games. Many fit nicely into the fanfare style that characterizes the

opening ceremonies; others capture the solemnity of the occasion, culminating in the

Olympic Oath. Taken together, they provide a splendid soundtrack not only for the

centennial of the modern Olympics, but for the entire drama of the Olympic phenomenon.

Time and again Williams, in a recent interview with William Guegold (author of 100 Years

of Olympic Music), speaks of the “mythological” inspiration the Olympics have

brought him—a notion not lost on those who have followed his scores for the Indiana

Jones films (and all the mythos they contain), his theme for Superman, or his music for

Close Encounters of the Third Kind. For Williams, this mythological measurement evokes a

certain sense of scale. “You don't write the same kind of piece that you;re going to

play for an audience of 1,000 as you're going to play out on the Esplanade for an audience

of 250,000. You can still have a lot of notes; it [the large-scale work] doesn't have to

be simple, but it seems to me that the line has to be like a big arc.”

This “big arc” might refer as much to the works by other composers featured here

as his own, but among present-day composers, few have taken such possession of the

“big arc” as Williams. From the spectacular antiphonal brass choirs that open

and recur in Summon the Heroes, the Official Theme of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games,

to the polyrhythms that describe the theme's close, Williams' piece provides a wonderful

example for the collection as a whole.

As the Baron noted, it is the struggle, not the triumph, that matters most in the Olympic

Games. Williams and his fellow composers have succeeded in capturing the idea that the

very existence of these Olympics is so enobling that, for a brief time at least, we care

not who wins and who loses. Every player who marches out onto the field during the opening

ceremonies, regardless of his or her event or country of origin, is taking up the

challenge of humanity, and the stuggle to face the limitations and frailties of humankind.

And in each player resonates the music that transcends all barriers of differentiation.

Jackson Braider

|