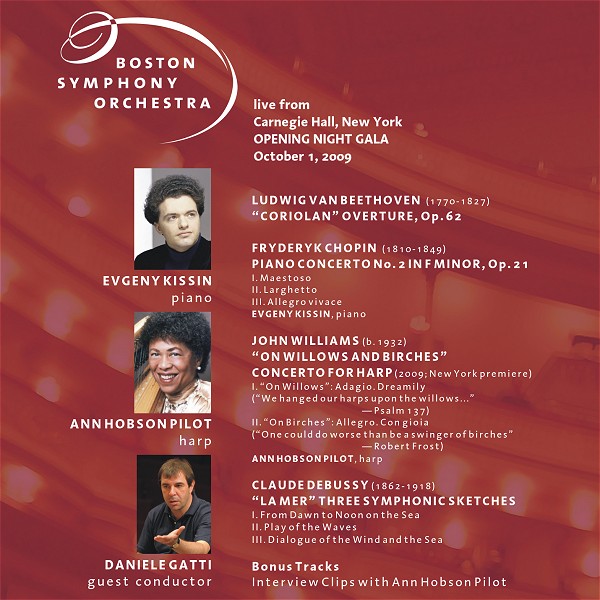

OPENING NIGHT GALA

The Opening Night of Carnegie Hall's 119th Season

Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage

Thursday, October 1, 2009 at 7 PM

BEETHOVEN

Coriolan Overture, Op. 62

CHOPIN

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 IN F MINOR, OPUS 21

- Maestoso

- Larghetto

- Allegro vivace

EVGENY KISSIN, piano

WILLIAMS

“ON WILLOWS AND BIRCHES,” CONCERTO FOR HARP AND ORCHESTRA (NY Premiere)

- “On Willows”: Adagio. Dreamily

(“We hanged our harps upon the willows...”—Psalm 137)

- “On Birches”: Allegro. Con gioia

(“One could do worse than be a swinger of birches” — Robert Frost)

ANN HOBSON PILOT, harp

DEBUSSY

“LA MER,” THREE SYMPHONIC SKETCHES

- From Dawn to Noon on the Sea

- Play of the Waves

- Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea

Encores:

LISZT

Soirées de Vienne (Valses caprices d’après Schubert), No. 6

CHOPIN

Waltz in D-flat Major, Op. 64, No. 1, "Minute"

Bonus Track: Interview with Ann Hobson

Pilot

Ann Hobson Pilot

Evgeny Kissin, Daniele Gatti

Substitute Conductor,

Solid Concert

Italian conductor Daniele Gatti, a

last minute substitute for James Levine,

leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Debussy's "La Mer."

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI, New

York Times

Published: October 2, 2009

It took a lot of last-minute

scrambling, but the Boston Symphony Orchestra found a

suitable substitute to take the place of James Levine for the concert on Thursday night

that

opened the 119th season at Carnegie Hall: the Italian conductor Daniele Gatti.

Only on Tuesday did word come that Mr. Levine would have to withdraw because of a

herniated disk in his back that required immediate surgery. One of the Boston

Symphony’s

gifted assistant conductors could have stepped in. But the orchestra wanted a known

maestro for this prestigious event.

Mr. Gatti, the music director

of the Orchestra National de France and the chief conductor

of the Zurich Opera, who has regularly conducted the Boston Symphony, happened to be

in New York rehearsing Verdi’s “Aida” at the Metropolitan Opera, a run that

opens on

Friday. He made just one change in the program Mr. Levine had chosen, replacing

Berlioz’s “Roman Carnival” with Beethoven’s “Coriolan”

Overture. All in all, he drew strong

performances from the players, including a highly individual, muscular and intriguing

account of Debussy’s well-known “La Mer” to conclude the concert.

Mr. Gatti opened with the

Beethoven, a stern, weighty work that sounded even more so

here. He reined in the tempo and emphasized the heaving density of the music. He had

the piece sounding like an ominous Verdi overture. At times the energy slackened and

nearly turned ponderous. Still, I admired Mr. Gatti’s willingness to make a statement

with

this piece.

The brilliant Russian pianist

Evgeny Kissin was the soloist in Chopin’s Piano Concerto No.

2. He and Mr. Gatti had never worked together until a rehearsal in Boston on Wednesday.

But Mr. Gatti seemed a temperamental and musical match for the rhapsodic Mr. Kissin in

the performance they gave here.

Mr. Kissin’s Romantic

approach to Chopin is not to all tastes. His generous use of rubato

to draw maximum expressivity from phrases was sometimes too much. I tend to prefer

Chopin a little more straightforward, more Classical.

Still, this is a question of

taste. Mr. Kissin is a phenomenal pianist and a sensitive

musician. He produced wondrous colorings and, in fortissimo outbursts, played with

scintillating yet unforced sound. Though Chopin intricately embellishes his melodic lines,

Mr. Kissin made every note matter: nothing was ever just passagework. He played the

wistfully elegant Larghetto with ethereal textures and poetic grace. Best of all was the

finale, rather like a slightly forlorn mazurka. And he played the spiraling virtuosic

flights

with impressive clarity and uncanny delicacy.

Mr. Kissin is typically

generous with encores, even when appearing with orchestras. He

granted his cheering audience two on this night: a dashing account of Liszt’s

“Valse

Caprice” No. 6, after Schubert, and a breathless Chopin “Minute” Waltz that

seemed to last

not much more than a minute.

Ann Hobson Pilot, the former

principal harpist of the Boston Symphony, who recently

retired after 40 years with the orchestra, was the soloist in John Williams’s

“On Willows

and Birches,” written for her, a work that had its premiere on Sept. 23 in Boston.

Though

Mr. Williams made his name (and his fortune) as a film composer, he is a smart craftsman

of concert works.

The first movement of this

15-minute piece, inspired by a phrase from Psalm 137, “We

hanged our harps upon the willows,” is alluring, atmospheric music that balances lacy

runs

and dry plucked themes in the harp with quizzical, elusive harmonies and shimmering

orchestral textures. It reminded me of Mr. Williams’s transfixing score for the film

“A.I.” The

jaunty second movement, inspired by the Robert Frost poem “On Birches,” was less

engaging. The music is jazzy and restless but a little square and tame, like a pops

concert

“Petrouchka.” Ms. Pilot was a refined and nimble soloist. Mr. Gatti, who learned

this score

during a car trip to Boston the day before the concert, seemed in full command.

The Boston S ymphony and the Met have to be worried about the implications of Mr.

Levine’s recurring ailments. At 66, he is trying to hold down two of the biggest jobs

in

American music, something that would test a completely healthy younger conductor.

But that is another question. Thanks to Mr. Gatti, Carnegie Hall’s season is off to a

solid

start.

At Carnegie gala, sub

conductor displays heroics

Oct 2, 2:36 PM EDT

By Martin Steinberg, Associated Press

NEW YORK (AP) -- A not so

funny thing happened on the way to the opera.

Italian conductor Daniele Gatti arrived in New York from Japan 1 1/2 weeks ago to lead

"Aida" at the Metropolitan Opera, his first appearance there since 1995. Then,

two days

before the gala opening of Carnegie Hall's 119th season, the scheduled conductor, James

Levine, canceled all commitments through December to undergo back surgery.

Hours after the cancellation announcement, the 47-year-old Gatti finished the dress

rehearsal for "Aida" for Friday night's Met performance and agreed to fill in

for Levine and

lead the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie's Thursday night opener.

At dawn Wednesday, he left for Boston, studying the score of John Williams' newly

composed harp concerto as he was driven there for a 2 1/2 hour rehearsal. Gatti, the

orchestra, harpist Ann Hobson Pilot and pianist Evgeny Kissin rehearsed for two more

hours in New York on Thursday.

If that were not enough

heroics, Gatti donated his five-figure fee to the BSO in honor of the

67-year-old Levine, who is being treated for a herniated disk.

The performance got off to a

rocky start. Because Gatti was uncomfortable with the

scheduled first number, Berlioz's "Roman Carnival" Overture, he opted for

Beethoven's

"Coriolan" Overture. The opening attacks were jagged rather than precise. The

tempi were

plodding and unexciting. Despite some thrilling music, the performance was dull.

Things got better with

Chopin's Piano Concerto No. 2. Gatti led the orchestra in a smooth

accompaniment to Kissin's magnificent solo performance. It's a work that won Kissin world

attention when he first performed it in his native Moscow in 1984 at age 12.

Now, nine days before his 38th

birthday, Kissin was at it again. Agitated sections were

filled with brio, Kissin's lyrical lines were dreamy, his runs flawless, his pauses

pregnant

with anticipation. After a three minute standing ovation, he rewarded the audience with

two

solo encores - charming runs through Liszt's "Soirees de Vienne (Valses caprices

d'apres

Schubert)" No. 6 and Chopin's "Minute Waltz" (which actually took a minute,

41 seconds).

After intermission, Gatti

faced Williams' "On Willows and Birches," which had its world

premiere only a week earlier by Pilot, Levine and the BSO. The Hollywood composer and

former leader of the Boston Pops wrote the concerto for Pilot in honor of her retirement

this summer. The two had collaborated in Boston for 13 years.

The first movement is inspired

by Psalm 137, a lament of the Israelites in exile in Babylon:

"We hanged our harps upon the willows." The music is more ethereal than

mournful, with

the nearly constant harp towering over the soft musical cushion provided by Gatti.

The second movement is a joyous, Bernstein-like, romp on Robert Frost's poem

"Birches."

("One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.") Gatti's quick study in the

car paid off.

He kept the orchestra under control as Pilot artfully breezed through her part.

The final number was Debussy's

"La Mer." Despite not having performed this complicated

work since November 2006, Gatti conducted it by memory. Through the impressionistic

undulations, shimmering melodies, flittering asides and stormy agitations, Gatti led a

memorable account.

For Gatti, who is music

director of the Orchestre National de France, his first performance

at Carnegie Hall in 12 years ended on a truly triumphant note.

John Williams Remembers

‘Jaws’ as Harp Concerto Opens Carnegie

Interview by Zinta

Lundborg, Bloomberg.com

Oct. 1 (Bloomberg) -- Looking

back on sharks and ahead to Tintin’s dog, Oscar-winning

composer John Williams described his new ode to a few favorite trees.

This is the harp concerto that

the Boston Symphony plays tonight as Carnegie Hall opens

for the season without the orchestra’s maestro -- James Levine needs back surgery and

Daniele Gatti will take his place.

The busy 77-year-old composer

(“Star Wars,” “Jaws,” “ET,” “Schindler’s

List’’) spoke by

phone from his studio in Los Angeles.

Lundborg:

“On Willows and Birches” is inspired by Psalm 137 and Robert Frost. How

does text lead to music for you?

Williams:

I occasionally read about trees, as I guess we all do, and there was a picture of

a famous willow in England with a caption quoting the psalm: “There on the willows we

hung our harps.” I just thought: What a wonderful picture of harps hanging in the

trees in the evening, wind

wafting through them, creating a beautiful, unearthly sound.

Lundborg:

What are you currently working on?

Williams:

Steven Spielberg is doing a motion-capture rendition of “Tintin,” which is a

cartoon popular in Europe, with wonderful original graphics by Herge. I’m composing

music for that now.

Lundborg:

Do you already have a cute canine theme for Tintin’s fox terrier, Snowy?

Williams:

Yes, I do.

Lundborg:

When you wrote that two-note motif for “Jaws,” when did you know that it was

going to do the trick?

Williams:

When I played the score on the piano for Spielberg, we just laughed about it,

wondering if such a simple device could be effective.

The force it can generate is not unlike the shark’s power. It has an unstoppable,

primeval,

simple but tremendously strong energy.

Lundborg:

Most of the people on the planet can hum your melodies. Is coming up with

them the hardest part of your job?

Williams:

It’s the part that I spend the most time on. Usually the results are not

complicated, but the most challenging part is to get down to the essence of something in a

few short measures.

Lundborg:

“Star Wars” has often been called the greatest score ever written. Is it at the

top of your list?

Williams:

We always see things we wish we can improve and others we take a little pride

in. My personality is such that I always want to look forward and hope I can do better.

Lundborg:

You’ve done everything, so at this stage of your career, what brings you the

most pleasure?

Williams:

To surprise you, I don’t know if I think of it exactly that way. It’s all very

pleasant,

but it’s certainly work for me. I write music almost all the time.

I need to work these musical problems out in my mind, and it’s a 24-hour-a-day

process.

Many times, I sit up in the middle of the night and say, “Aha, that’s the

progression, or

that’s the tune.”

Lundborg:

What do you do when you’re not composing?

Williams:

I try to walk an hour a day -- the winter weather is the best thing about living in

L.A. -- and I read a lot more than I listen to music.

Lundborg:

You don’t have an iPod?

Williams:

No. When I’m writing, it’s not helpful to listen to music, especially great

music.

When I do listen, I want to hear something like Haydn, which seems to me so true and so

joyful.

Lundborg:

How is technology affecting music?

Williams:

The future of music itself is certainly going to be wedded very closely to the

development of technologies and audio-visual couplings. Serious composers now are very

interested in film.

Lundborg:

Will live players be rendered obsolete?

Williams:

To a certain extent, they already have been. On the other hand, there is no

substitute for human expression and the beauty great players can bring.

Lundborg:

You helped plan the festivities welcoming 28- year-old Gustavo Dudamel as

music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. I hear the Hollywood Bowl on Saturday

sold out in just over an hour. A sign of hope for classical music?

Williams:

It’s great to have new energy, new generations and new genius, and we have in

Gustavo the charisma of a young Leonard Bernstein, Yo-Yo Ma or Itzhak Perlman.

It’s so reassuring to know we are capable as a species of producing these creatures.

(Zinta Lundborg is a

writer for Bloomberg News. The opinions expressed are her own. This

interview was adapted from a longer conversation.)

A big THANK YOU to Miguel Andrade!

|