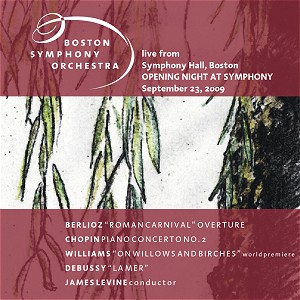

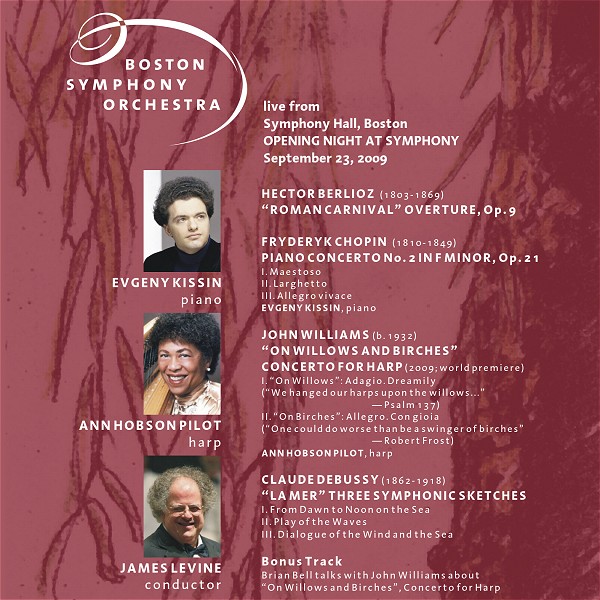

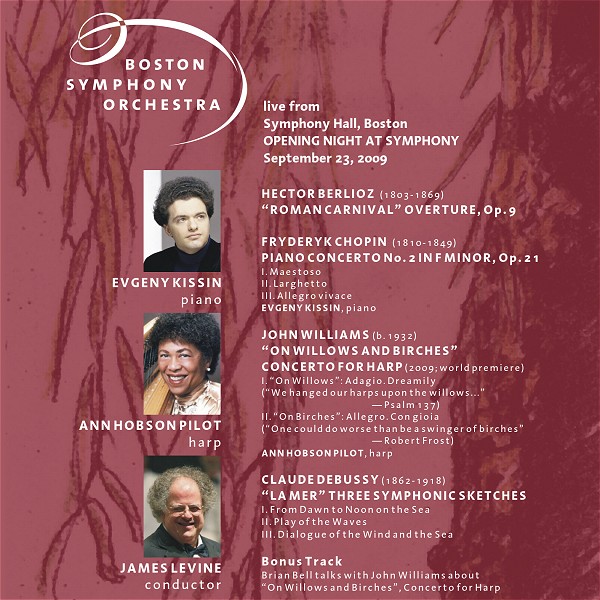

OPENING NIGHT AT SYMPHONY

BERLIOZ

“ROMAN CARNIVAL” OVERTURE, OPUS 9

CHOPIN

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 IN F MINOR, OPUS 21

- Maestoso

- Larghetto

- Allegro vivace

EVGENY KISSIN, piano

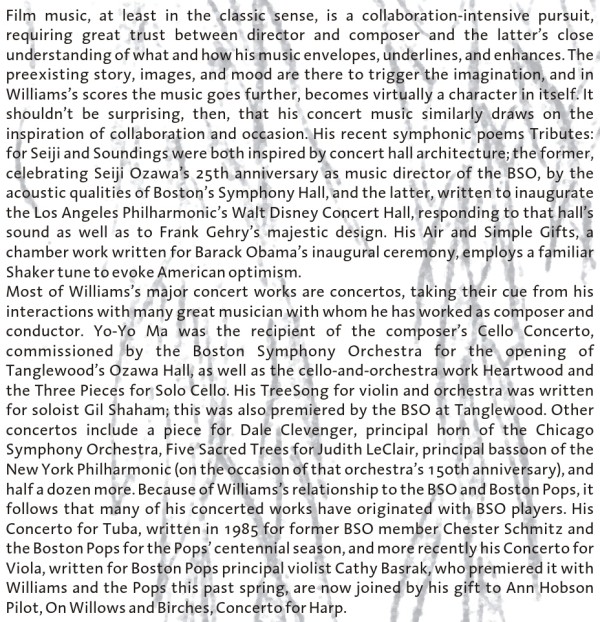

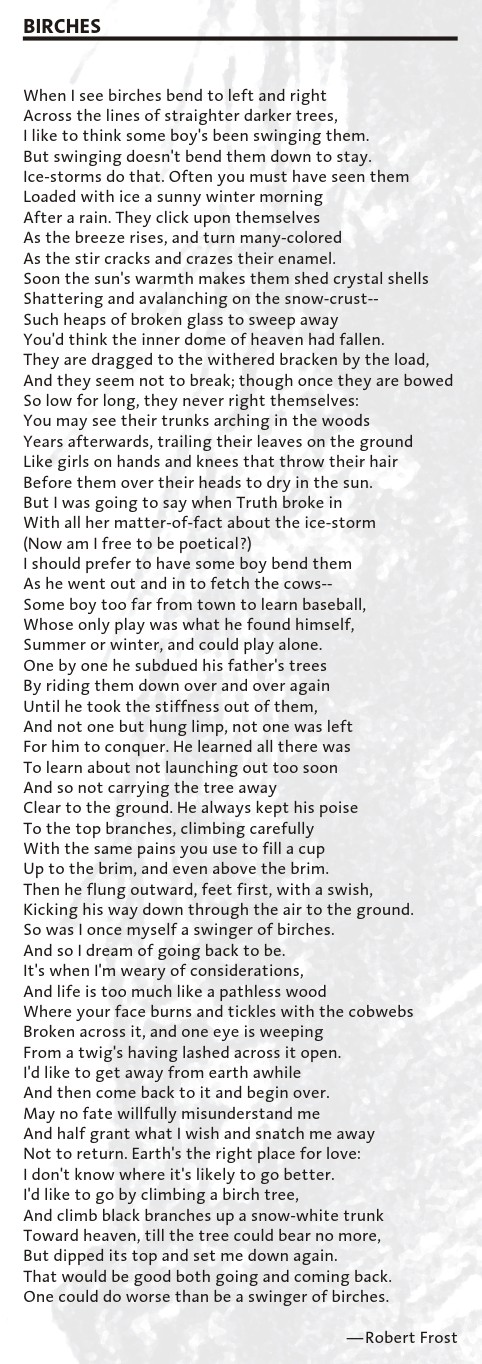

WILLIAMS

“ON WILLOWS AND BIRCHES,” CONCERTO FOR HARP AND ORCHESTRA

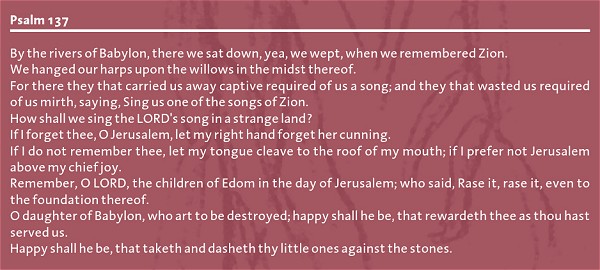

- “On Willows”: Adagio. Dreamily

(“We hanged our harps upon the willows...”—Psalm 137)

- “On Birches”: Allegro. Con gioia

(“One could do worse than be a swinger of birches” — Robert Frost)

ANN HOBSON PILOT, harp

DEBUSSY

“LA MER,” THREE SYMPHONIC SKETCHES

- From Dawn to Noon on the Sea

- Play of the Waves

- Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea

Bonus Track: Brian Bell

talks with John Williams about "On Willows and Birches", Concerto

for Harp

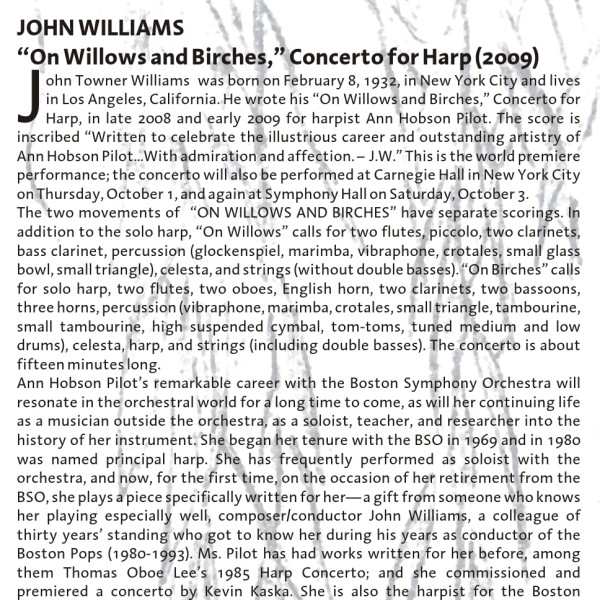

John Williams,

Ann Hobson Pilot

Groundbreaking master of

angelic instrument set to take wing

By Geoff Edgers, Boston Globe

Globe Staff / September 22, 2009

Ann Hobson Pilot spent four

decades with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. (Dina Rudick/Globe Staff)

One day in high school, Ann

Hobson Pilot, an aspiring harpist who happened to be African-

American, was at a friend’s house when the girl’s mother pointed to a picture on

the wall. It

showed a white woman with flowing blond hair. “Now she looks like a harpist is

supposed to,’’

the woman said with an edge.

Hobson Pilot still remembers

the sting of the comment, even a half centur y later. She

remembers it as she prepares for the highlight of her four decades with the Boston

Symphony Orchestra, tomorrow night’s premiere of a concerto written for her by John

Williams.

“It surprises me when I think back to that time,’’ says Hobson Pilot, now

65. “I worked hard,

but what was I thinking? The harp was considered to be the instrument of an angel, a

white woman with flowing gowns.’’

From the Symphony Hall stage,

Hobson Pilot changed that perception.

“No one thinks of Ann Hobson Pilot as an African-American harp player,’’

says Mark Volpe,

the BSO’s managing director. “They think of her as the great harp player of her

time.’’

The BSO is making that point by featuring Hobson Pilot in programs to celebrate her

recent retirement, including a starring role in tomorrow’s opening-night gala and

October

concerts in Carnegie Hall and S ymphony Hall.

The honor is unprecedented at

the BSO, where senior players typically take their farewell

bow at the orchestra’s summer home at Tanglewood. Hobson Pilot is anything but

typical.

She tried to retire three years ago. Music director James Levine pleaded with her to stay,

and she did. Now, though, she’s ready. She wants to travel, play solo recitals, and

perform with other

orchestras. “My main goal was to leave before my playing went downhill,’’

Hobson Pilot said during a

recent interview at Symphony Hall. “I feel that way about parties. I’d rather

leave early than

stay too long.’’

Growing up in Philadelphia,

Hobson Pilot was surrounded by music. Her mother and older

sister both played piano. She decided, at age 14, to take up a different instrument. At

school, she asked her music teacher about flute, cello, and violin. Other students had

already taken those instruments. The harp was available.

Her parents paid $15 a month

to rent a rickety harp for her to practice on. They also

bought a used green Rambler station wagon to transport the instrument.

As a teenager, Hobson Pilot attended a summer harp camp in Maine and studied at the

Cleveland Institute of Music.

She landed a gig with the

National S ymphony in Washington after her 1966 graduation

and remained there until 1969, when Boston Pops conductor Arthur Fiedler suggested she

audition for the BSO. (Fiedler knew her from stints conducting the National Symphony.)

At the time, the only other African-American in the orchestra had been Ortiz Walton, a

double bass player from 1957 to 1962. Hobson Pilot won a permanent post in 1969 as

second harp. She was appointed principal in 1980.

In her new job in Boston,

Hobson Pilot didn’t push for diversity. She was there to play.

“I was quiet. Still am,’’ she said. “I didn’t get into making a

political presence. My statement

was doing my job and showing that playing music well had nothing to do with color. If

intelligent people looked at me, they’d acknowledge that.’’

But Hobson Pilot didn’t

ignore the issue of race entirely. Her husband, Prentice Pilot, a

bass player in the Boston Pops Esplanade Orchestra for 22 years, became the first artistic

director of Project STEP, a BSO program founded in 1982 to support minority players.

Hobson Pilot volunteered to work with the students.

She also insisted on having

her picture on the cover of compact discs she recorded. She

wanted African-American children to see that a woman with dark skin could star in the

classical world.

The reality is that Hobson

Pilot leaves a symphony world that hasn’t changed much for

African-Americans. Just a handful of black players serve as principals nationwide. The

percentage of African-American musicians in American orchestras has ranged from just

1.4 percent to 1.9 percent over the last eight years.

The trouble, Hobson Pilot and

Volpe believe, is not at the orchestra level, particularly

because auditions are conducted behind a screen, making it impossible for members to

rule out musicians based on appearance.

“You start with the

fundamental of what’s happening in major school districts,’’ said the

BSO’s Volpe. “There’s been an erosion of music programs.’’

With Hobson Pilot’s exit,

only one African-American player will remain in the BSO, cellist

Owen Young.

“I often tell her, you

can’t leave me here, I’ll be all alone,’’ joked Young, who joined the

BSO in 1991. “The truth is, what I got from her is professionalism. She comes and

plays

and is always prepared. It really has nothing to do with race or gender.’’

The Williams concerto came

about because Hobson Pilot admired the composer’s writing

for harp in his scores for “Schindler’s List’’ and “Angela’s

Ashes.’’ She called Williams last

year to request a composition, but he declined.

His reluctance stemmed from

both his busy schedule and the challenges of writing for solo

harp. “I kept saying, ‘Ann, there are so many wonderful composers out

there,’ ’’ Williams

recalled. “But she said, ‘No, I want you to do it.’ In the end, I found I

couldn’t resist her.’’

On a recent day, Hobson Pilot sat on a chair on the Symphony Hall stage with her harp.

She tilted the instrum ent back and began to play the Williams piece, “On Willows and

Birches.’’

“For me to play a piece

for John Williams is incredible,’’ she said, her harp leaning into her.

“And to play with the BSO with Levine conducting. Please . . .’’

BSO opens season by

honoring one of its own

By Jerem y Eichler, Boston Globe

Globe Staff / September 24, 2009

The BSO honored Ann Hobson Pilot, the former

principal harpist who retired this summer after a four-decade

career with the orchestra. (Michael J. Lutch)

From a musical perspective,

opening nights of orchestral seasons are often fairly formulaic

affairs: one part star soloist, one part fizzy standard repertoire, then OK let’s

head to

dinner. At last night’s opener in S ymphony Hall the Boston Symphony Orchestra tried

admirably to tweak the annual routine, not so much by altering the template as by adding

to it.

There was still a well-known

soloist (pianist Evgeny Kissin) and familiar masterworks

(including Debussy’s “La Mer ’’), but the BSO also seized the moment

to honor one of its

own, Ann Hobson Pilot, the former principal harpist who retired this summer after a

distinguished four-decade career with the orchestra. The honoring was also done in the

best possible way: by the commissioning of a new work. Pilot chose John Williams as the

composer to pen her tribute, and the new work, “On Willows and Birches,’’

was unveiled

last night. It was the first time a BSO opener featured a premiere since 1980, when Seiji

Ozawa led Bernstein’s “Divertimento.’’

James Levine was on the

podium, looking energetic as he led a spacious and tonally

generous account of Berlioz’s “Roman Carnival’’ Overture, with Robert

Sheena floating a

poised English hor n solo and the brass section erupting with some fiercely festive

volleys

in the final pages of the score.

Kissin first made his name

with the Chopin piano concertos, and they still flow effortlessly

from his fingers, at least judging by last night’s technically brilliant account of

Piano

Concerto No. 2. You had to admire the astonishing fluidity and clarity of his passagework,

though there was also a certain emotional chilliness that hovered over his playing. It was

a

pleasant surprise when a solo encore - a Schubert-Liszt Valse-Caprice from “Soirees

de

Vienne’’ - brought out a touch more warmth, fantasy, and openness.

After intermission came the

new Williams work, a well-crafted two-movement concerto that

clearly fulfills its stated aims of paying tribute to Pilot and showcasing her formidable

musicianship. That said, it is a modest work in its musical substance and in its effect.

The

first movement, titled “On Willows’’ after a line from Psalm 137, is slow,

spare, and

ruminative, with an undulating solo harp line drifting above a hazy orchestral landscape,

creating a kind of spectral chamber music that seems to be heading somewhere it never

quite reaches. The second movement, “On Birches’’ after the Robert Frost

poem, is more

chipper, caffeinated, and rhythmically emphatic, with an extended cadenza that puts the

soloist’s virtuosity squarely on display.

And Pilot had plenty of it to

show this appreciative audience. Her playing had impressive

rhythmic clarity but also a keen sense of mood and color, not to mention a fundamental

graciousness and expressive warmth. As the crowd’s ovation made clear, she will be

missed.

Boston Symphony

Orchestra opens new season with flourish of excitement

By Keith Powers, Boston Herald

Thursday, September 24, 2009

In a splashy season opener,

complete with a high-profile conductor (James Levine),

renowned soloist (Evgeny Kissin), and world premiere from the best-known composer on

the planet (John Williams), the Boston Symphony Orchestra began its 129th season in

grand style last night at Symphony Hall.

Tuxedos and gowns were the

uniforms of choice, but the glitter in the audience was no

match for the mega-wattage onstage. The program began simply enough with Berlioz’s

“Roman Carnival Overture,” which Levine amped up in excitable fashion. That

brought out

Kissin, and the redoubtable Russian served up a glorious reading of Chopin’s Second

Piano Concerto.

The young Chopin, only 20 when

he wrote this, knew how to serve the greatest musician

he knew - himself. Yet while this concerto honors the soloist, it avoids mindless

virtuosity,

and remains thoroughly appealing and accessible. Fluid and confident, Kissin’s

playing

captured every inherent emotion.

Williams was commissioned to

write a harp concerto to honor the BSO’s retiring principal,

Ann Hobson Pilot, who leaves after 40 years. “On Willows and Birches” lasted

about 15

minutes, in two decidedly different movements, and showed the composer at his best. The

music was accessible without sounding simplistic.

The first movement, inspired

by Psalm 137, airily conjured the musical atmospheres one

expects from the harp. The second movement bore a bouncy sense of rhythmic invention,

never settling on a steady beat but investigating shifts in pulse throughout.

The evening concluded with a

boisterous presentation of Debussy’s “La Mer,” with the

maestro eager to accent the extremes.

The Last Pluck: BSO

Harpist Retires After 40 Years

By Andra Shea, wbur.org

Published September 23, 2009 (Updated September 24)

Boston Symphony Orchestra harpist

Ann Hobson Pilot (Andrea Shea/WBUR)

Ann Hobson Pilot officially

ended her 40-year tenure with the BSO last month, but she said

she doesn’t feel like she’s retired at all.

“It won’t feel like

that for a few weeks, I think,” she said, laughing.

That’s because she’s

been working harder than ever preparing for the premiere of a new

work by busy Hollywood composer John Williams. His tribute to Hobson Pilot is called,

“On

Willows and Birches, Concerto for Harp.”

“There’s something

heavenly — or even divine — if you like, about the harp,” Williams

said, “I think it has this special connection with the other-world.”

Ann Pilot Hobson fell under

the harp’s mysterious spell when she was 14 years old,

because it was so different. She said she was, too.

“When I was coming up, I

was an oddity being an African-American harpist, ” Hobson Pilot

said. “The harp was considered to be first of all a feminine instrument and certainly

not an

instrument of people of color. I mean the angels played the harp and all of that.”

Hobson Pilot’s harp playing got her into the Cleveland Music Institute. Then she won

a job

with the Washington National Symphony, where she was the first and only African-

American musician.

Next, in 1969, Hobson Pilot

remembers when Arthur Fielder came to guest conduct.

“And he said, ‘We have an opening in Boston for the principal of the Pops and

2nd with the

BSO and I like your playing — would you consider auditioning for the job?’

”

She did. And she won, recalled Bill Moyers. He played trombone for the BSO when

Hobson Pilot got the job.

“When I joined the

orchestra in 1952, there was one other person in the orchestra who

was a woman,” Moyers said. “One. And she was the second harpist. All the rest

were men.

And there were no people of color.”

Hobson Pilot came on in 1969.

Today, with her retirement, there is only one full-time African-American member left in

the BSO.

But Moyers is quick to remind me of the blind audition process. It all happens

behind a screen and is fully based on musical skill.

Hobson Pilot, he said, was hired for no other reason than her beautiful playing.

“She has poetr y inside of her,” Moyers said. “What more could you hope

for?”

The harpist admits she is disappointed by the lack of diversity in the classical music

world,

but she’s not bitter. It’s brutally competitive, Hobson Pilot says, and

there’s a lack of early

music education opportunities for minorities.

She’s been a role model

for school children in Boston, but it’s anything but child’s play

working full-time for a major music organization like the BSO.

“This orchestra plays

perfectly,” Hobson Pilot said, laughing, “and you know, being a part

of the orchestra, you have to be perfect. So for 40 years tr ying to be perfect has been a

challenge.”

But BSO Managing Director Mark

Volpe said she rose to it, again and again.

“It’s an instrument where you can’t hide, it’s out there, and I

don’t remember Anne

screwing up,” Volpe said. “I mean she’s amazingly consistent.”

Volpe is not the only one to

think that. Composer John Williams has never written a

concerto for the harp, and admits he was reluctant to take on the challenge.

“There are difficulties with harp,” Williams said. “Limitations, special

opportunities, people

will understand there are seven pedals and each string can produce three different pitches

— it can be a C flat, a C natural or a C sharp at any given time.”

But Williams said Hobson Pilot

won him over, and he finished the piece.

“I stretched it and I actually wondered if she could play it all,” he confessed.

“I was

surprised that she could — it seems almost like a magic trick to hear and watch her

do it.”

On stage at Symphony Hall, John Williams rehearsed “On Willows and Birches, Concerto

for Harp” with Hobson Pilot. Sitting on a cushioned stool, she embraced her heavy

harp

with her entire body. Her two feet tapped the seven-foot pedals as her nimble fingers

plucked and glided across the 47 strings.

Hobson Pilot said when

Wednesday night’s concert is over, she’ll miss her seat on stage

very much.

“Sitting in the middle of

that wonderful BSO sound for 40 years has been beyond belief,”

she said, but added, “I’ll be able to sit in the audience and hear it from a

different

perspective.”

Again, the harpist laughed.

Ann Hobson Pilot’s final concert with the BSO is Oct. 3 in Boston, but she’ll

get to kick off

the season at Carnegie Hall in New Yor k on Oct. 1.

______________________

Corrections:

An earlier version of this

story, an accompanying video, and the broadcast

version of this story incorrectly stated that Gibson Pilot was first African-American

musician

hired by the BSO; in fact, she was the first African-American woman hired. The earlier

story also incorrectly stated the location of Gibson Pilot’s final performance; it

will be at

Boston Symphony Hall on Oct. 3.

Boston Symphony Orchestra To Honor

Harpist

Sep 23, 2009 10:07 pm US/Eastern

BOSTON (WBZ)

The Boston Symphony Orchestra's principal

harpist, and first female

African-American to join, is retiring after 40 years.

Ann Hobson Pilot will be the featured

soloist at the BSO's opening night performance

Wednesday night. She'll be given a retirement gift never given to a member before.

Top Hollywood composer John Williams, the man behind the scores to Superman, Star

Wars, and Harry Potter, has written a piece for Ann called "On Willows and Birches,

Concerto for Harp."

"We are celebrating not just a great

harpist, but a great teacher and a great human being

and a great woman," Williams says.

He adds, "Every string on the harp has

three pitches. They're constantly being re-tuned by

foot petals and synchronized with hand action - so it is a magic trick that ver y few

people

on earth can perform with the kind of skill and art that Ann Hobson Pilot does."

Ann considers it an honor. "It's the greatest gift anybody could give anybody else,

with the

possible exception of life," she says.

Ann picked up the harp at 14 years old. She

attended a high school in Philly that she says

fortunately for her, had a harp. She's never looked back. She joined the BSO in 1969 and

was appointed to principal harp in 1980.

She tried to retire years ago, but Maestro

James Levine begged her to stay. Now, she's

finally ready.

"I was emotionally ready, physically,

spiritually, financially ready to leave."

She'll perform "On Willows and Birches" for opening night, at Carnegie Hall

October 1st,

then again, for her final performance on October 3rd, with the BSO.

A big THANK YOU to Miguel Andrade!

|